Edges, boundaries, urban walls and limits: a brief project survey.

The image of a medieval fortress complete with walls, battlements and towers is a strong historic precedent for containment of built form. Circling a town or cluster of buildings, fortifications present a neat expression of an urban boundary. By contrast, many early Australian towns were defined by settlement plans which laid out (non-visible) title boundaries within square mile town reserve . Around the township centre ‘Suburban Lots’ extended to a five mile limit, beyond which were ‘Country Lots’ . Urban growth and the movement of people and goods (and therefore wealth) was not controlled or supervised by means of architectural or urban form . Nevertheless, fortifications (walls, battlements, towers, castellation etc) could be described as archetypical structures. That is, structures that resonate strongly at a symbolic level regardless of historic or cultural associations.

The plan of the fortress of Carcassonne , France, illustrates its urban function of containment and control. In this instance, the main wall is fortified by regular watch towers as well as the creation of a lesser outer wall. Entry is through limited control points: historically a point for tax collection. As a result any visitor is quite clearly inside or outside the urban walls. As Lewis Mumford describes “the wall…served as both a military device and an agent of effective command over the urban population. Esthetically it made a clean break between city and countryside; while socially it emphasized the difference between insider and outsider.”

Contained within is the medieval urban structure which once supported all the needs of its inhabitants should they be under seige; food storage, religious buildings, cramped living quarters etc. The contemporary Carcassonne has grown well beyond this structure but the presence of the fortress is still a defining urban characteristic, for example, easily read from Google Earth.

The enduring separating function of the urban wall is alive in contemporary Rome where the historic practice of naming places or buildings after their relative location to the ancient city walls, for example, Basilica Papale S Paulo Fuori Le Mura translates to the Papal Basilica Outside The Walls), is extended to everyday conversation. Bus stops, post offices, market places are all in described as either inside or outside of the walls.

The historic task of population containment and control also existed at much larger scale; that of the landscape or region. Structures such as Hadrian’s Wall (AD122) and the Great Wall of China (completed during Ming Dynasty) were built for both military and economic purposes. Hadrian’s Wall has been measured at around 117.5 km long giving an idea of the massive scale of this type of structure. The image shown here of Hadrian’s Wall shows how the materials, form and location have drawn from the site itself. Opportunistically, the wall and some associated structures (possibly for buildings used for surveillance) are built along the escarpment edge. Here the relationship between infrastructure, architecture and landscape is symbiotic.

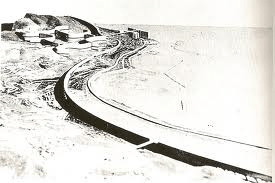

During the nineteenth century the effectiveness of walls and fortifications were reduced by advancing military technology: explosive artillery shells, aeroplanes, and so on. The ‘wall’ continued to be used but as a formal urban or architectural solution. In 1932, Le Corbusier produced his well-known scheme for Algiers, Plan Obus. This demonstrated how the wall as a powerful architectural gesture could visually and physically organise the urban and surrounding rural landscape. Although not strictly for military use, the wall in these schemes was still employed as a controlling device dominating the original and indigenous conditions. In her essay Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism Zeynek Celik’s writes: ‘Le Corbusier’s plan establishes constant visual supervision over the local population and clearly marks the hierarchical social order onto the urban image, with the dominating above and the dominated below’ . Celik explains further that the origins for the colonising ambition expressed in Le Corbusier’s scheme can be traced back into the nineteenth century via French colonial discourse, and that Plan Obus, despite being conceived well into the twentieth century clearly expresses the desire for command over ‘non-Western’ and ‘different’ people and places.

Several post-war decades later the ‘wall’ can be seen to be applied as more uniting and levelling urban structure through a number of social housing schemes built in Italy. They demonstrate a range of architectural and urban achievement. One of the more successful was the scheme lead by Luigi Carlo Daneri’s for Forte Quezzi , 1956. In this project the architectural morphology relates directly to the topography of the hillside it is located on, while terraces and balconies are directed to the views to the historic town centre of Genoa and harbour only three kilometers away. Less successful was the housing scheme for Corviale, built during the 1970s and located outside Rome. This design of the scheme, led by architect Mario Fiorentino, resulted in a 1000m long structure containing approximately 1600 apartments connected by a series of socially dysfunctional and dangerous spaces. Exacerbating the architectural failings it was constructed remotely from any of the established suburban areas of Rome.

From both an urban and cultural point of view Forte Quezzi could be described as an integrated solution while Corviale could be described as a segregated solution. And while neither project employs the linear block, or ‘wall’ as a boundary device they highlight the urban, architectural, social and cultural impact such massive structures have on the urban-scape or landscape the are sited within. The attributes of overlooking, a high number of dwellings in the same structure, and an unusually long building footprint are unavoidable and may benefit or detract from the scheme depending on context and application. Whatever their conditions under which these schemes have been successful or not, they clearly state the ambition shared by this research of building form acting at an urban scale giving formal definition of the limits of the city. These Italian linear megstructures are not, however, an appropriate design response to Melbourne’s UGB which, by its nature, is located at the least populous fringes of the city.

Steven Holl’s projects for Edge of a City appears to reject the wall as both an architectural and urban solution to the problem of the boundary. They explore alternative architectural typologies for the task of delineating a boundary to a series of cities in the USA. In Spiroid Sectors, for the city of Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas, the wall has turned in on itself, spiralling and overlapping to form a conglomerate of wrapped buildings around courtyards creating a dialogue between open public space and built form. These megastructures are strategically positioned between the urban sprawl and open prarie landscape. Stitch Plan , for Cleveland, Ohio, proposes a series of X-shaped interventions that are simultaneously architecture, landscape and infrastructure. As with Spiroid Sectors a boundary to the urban edge is implied rather than constructed, as the mind’s eye draws lines, like dot to dot, between structures and over terrain.

The most tightly implied of these boundaries is by the Spatial Retaining Bars project, located on the outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona. A series of elevated, rectilinear structures are closely sited, yet the ground plane, and implied boundary, remains permeable and open. Furthermore, the curved positioning of the structures comes to an end and the boundary, having had its geometry set, once again is projected by the mind out onto the landscape.

Overall Holl’s agenda is two-fold: ‘delineate the boundary between urban and rural’ in order to ‘liberate the remaining natural landscape and protect the habitats of hundreds of species of animals and plants.’ The schemes propose that a focus of population and activity at the edge of a city could form part of the solution, creating an urban edge and maintaining a limit, but in order to do that successfully a rigorous and multi-layered urban strategy is required. A variety of programs are proposed for the structures: housing, cultural facilities, public transport as well as programs that support recreational and environmental and agricultural activities.

While Holl’s schemes could be considered successful in many ways, they lack a grounded or site-specific quality, an aspect of design considered important for this research. The representation of the schemes occasionally suggests an architectural wonder that has simply landed on the place with aerial photographic montages that hold the propositions at a distance. Nevertheless, the question of a boundary to a city is presented in a thought provoking light. Here, the problem of spatial control is as much as a conceptual concern as a physical one. Crossing the boundary means passing through meaningful architectural spaces activated by an array of urban and non-urban programs and out to the other side; fuori le mura.

By contrast, landscape architect Michele Desvigne’s proposed plan for the city of Issoudin, France (2005) responds to the ambiguous urban/non-urban edge as a transitional zone rather than an edge requiring fortification. In his book he describes this condition as ‘the usual catastrophe’ found at a city’s edge. Desvigne proposes an overlapped condition in which patches of non-urban (productive, agricultural) landscape are inlaid onto and within the peripheral urban landscape of the city. These patches are designed as a series of public parks connecting resident with the landscape of and beyond the periphery of the city. The location and size of the insertions are informed by the historic subdivisions, which radiate outwards from the medieval town centre.

Desvigne’s proposal offers a landscape-directed solution rendering the peripheral condition as permeable and open. Furthermore, depending on your route either in or out of the city or, perhaps more interestingly, by circling the city via the park-like spaces, a multitude of experiences are on offer grounding park visitors in the specifics of the place while loosely ordering the ambiguous edge condition. It is a conscious departure of the city edge as a line. Rather than creating a ‘container that is simply to be filled,’ it ‘suggest[s] possible collisions’ between landscape, urban design and architecture. It represents a solution that is strategic over formal and one that is intentionally modifiable. Consequently, there is openness and flexibility to Desvigne’s scheme that is appealing from the point of view of this research. It demonstrates a design precedent that explores of both general and site-specific strategies at the scale of a city in its landscape.

Copyright 2015 Vanessa Mooney